I stood on a wide and desolate shore

And the night was dismal and cold.

I watched the weary rise, –

And the moon was a riband of gold.

Far off I heard the trumpet sound,

Calling the quick and the dead,

The long and rumbling roll of drums,

And the moon was a riband of red.

Dead sailors rose from out of the deep,

Nor looked not left or right,

But shoreward marched upon the sea,

And the moon was a riband of white.

A hundred ghosts stood on the shore

At the turn of the midnight flood,

They beckoned me with spectral hands,

And the moon was a riband of blood.

Slowly I walked to the waters edge,

And never once looked back

Till the waters swirled about my feet,

And the moon was a riband of black.

I woke alone on a desolate shore

From a dream not sound or sweet,

For there in the sands in the moonlight

Were the marks of phantom feet.

“Iron Bottom Bay” by

Walter A. Mahler, chaplain, USS Astoria

To pass the time on my commute to work, I often listen to audio books. Recently I have been researching the war in the pacific for my other blog: USS Hornet (CV-12) – A Father’s Untold War Story so I am currently listening to Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal by James D. Hornfischer. The poem above appears at the start of one of the chapters and hearing it while driving to work, I was very moved. I have been trying to find out if this is the entire poem or just an excerpt. I couldn’t find anything on the internet and I have enlisted the help of my local library. If I find there is more, I will be updating this posting with the rest of the poem. (A reference librarian came through. Full text now appears above). Father Walter A. Mahler is quite famous from World War II (if priests are permitted to have fame 🙂 ).

To pass the time on my commute to work, I often listen to audio books. Recently I have been researching the war in the pacific for my other blog: USS Hornet (CV-12) – A Father’s Untold War Story so I am currently listening to Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal by James D. Hornfischer. The poem above appears at the start of one of the chapters and hearing it while driving to work, I was very moved. I have been trying to find out if this is the entire poem or just an excerpt. I couldn’t find anything on the internet and I have enlisted the help of my local library. If I find there is more, I will be updating this posting with the rest of the poem. (A reference librarian came through. Full text now appears above). Father Walter A. Mahler is quite famous from World War II (if priests are permitted to have fame 🙂 ).

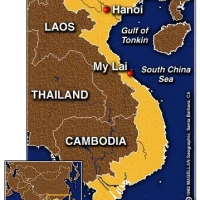

The Battle of Savo Island, also known as the First Battle of Savo Island and, in Japanese sources, as the First Battle of the Solomon Sea, and colloquially among Guadalcanal veterans as The Battle of the Five Sitting Ducks, was a naval battle of the Pacific Campaign of World War II, between the Imperial Japanese Navy and Allied naval forces.

The battle took place on August 8–9, 1942 and was the first major naval engagement of the Guadalcanal campaign, being the first of several naval battles in the straits later named Iron Bottom Sound, near the island of Guadalcanal. The battle was the first of five costly, large scale sea and air-sea actions affecting the ground battles on Guadalcanal itself, as the Japanese sought to counter the American offensive in the Pacific.

The battle took place on August 8–9, 1942 and was the first major naval engagement of the Guadalcanal campaign, being the first of several naval battles in the straits later named Iron Bottom Sound, near the island of Guadalcanal. The battle was the first of five costly, large scale sea and air-sea actions affecting the ground battles on Guadalcanal itself, as the Japanese sought to counter the American offensive in the Pacific.

In response to Allied amphibious landings in the eastern Solomon Islands, Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa brought his task force of seven cruisers and one destroyer down New Georgia Sound (also known as “the Slot”) from Japanese bases at New Britain and New Ireland to attack the Allied amphibious fleet and its screening force.

The screen consisted of eight cruisers and fifteen destroyers under British Rear Admiral Victor Crutchley VC, but only five cruisers and seven destroyers were involved in the battle.

Mikawa surprised and routed the Allied force, sinking one Australian and three American cruisers, while suffering only light damage in return. Mikawa’s force immediately retired following the battle without attempting to destroy the Allied transport ships supporting the landings.

The remaining Allied warships and the amphibious force withdrew from the Solomon Islands, temporarily ceding control of the seas around Guadalcanal to the Japanese. Allied ground forces had landed on Guadalcanal and nearby islands only two days before. The withdrawal of the fleet left them in a precarious situation, with barely enough supplies, equipment, and food to hold their beachhead. Mikawa’s failure to destroy the Allied invasion transports when he had the chance, however, would prove to be a crucial strategic mistake for the Japanese as it allowed the Allies to maintain their foothold on Guadalcanal and eventually emerge victorious from the campaign.

Background

Operations at Guadalcanal

On August 7, 1942, Allied forces (primarily U.S. Marines) landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida Island in the eastern Solomon Islands in order to deny the Japanese use for bases and the Allies wanted to use the islands as starting points for a campaign to recapture the Solomons, isolate or capture the major Japanese base at Rabaul, and support the Allied New Guinea campaign, then building strength under General Douglas MacArthur. The landings initiated the six-month-long Guadalcanal campaign.

The overall commander of Allied naval forces in the Guadalcanal and Tulagi operation was U.S. Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher. He also commanded the carrier task groups providing air cover.

U.S. Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner commanded the amphibious fleet that delivered the 16,000 Allied troops to Guadalcanal and Tulagi.

Also under Turner was British Admiral Victor Crutchley’s screening force of eight cruisers, fifteen destroyers, and five minesweepers. This force was to protect Turner’s ships and provide gunfire support for the landings. Crutchley commanded his force of mostly American ships from his flagship, the Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Australia.

The Allied landings took the Japanese by surprise. The Allies secured Tulagi, nearby islets Gavutu and Tanambogo, and the airfield under construction on Guadalcanal by nightfall on August 8. On August 7 and August 8, Japanese aircraft based at Rabaul attacked the Allied amphibious forces several times, setting afire the U.S. transport ship George F. Elliott (which sank later) and heavily damaging the destroyer Jarvis. In these air attacks, the Japanese lost 36 aircraft, while the US lost 19 aircraft, including 14 carrier fighter aircraft.

Concerned over the losses to his carrier fighter aircraft strength, anxious about the threat to his carriers from further Japanese air attacks, and worried about his ships’ fuel levels, Fletcher announced that he would be withdrawing his carrier task forces on the evening of August 8. Some historians contend that Fletcher’s fuel situation was not at all critical but that Fletcher implied that it was to justify his withdrawal from the battle area. Turner, however, believed that Fletcher understood that he was to provide air cover until all the transports were unloaded on August 9. Even though the unloading was going slower than planned Turner decided that without carrier air cover he would have to withdraw his ships from Guadalcanal. He planned to unload as much as possible during the night and depart the next day.

Japanese response

Unprepared for the Allied operation at Guadalcanal, the initial Japanese response included airstrikes and an attempted reinforcement. Mikawa, commander of the newly formed Japanese Eighth Fleet headquartered at Rabaul, loaded 519 naval troops on two transports and sent them towards Guadalcanal on August 7. However, when the Japanese learned that Allied forces at Guadalcanal were stronger than originally reported, the transports were recalled.

Mikawa also assembled all the available warships in the area to attack the Allied forces at Guadalcanal. At Rabaul were the heavy cruiser Chōkai (Mikawa’s flagship), the light cruisers Tenryū and Yubari and the destroyer Yunagi.

Japanese heavy cruiser Chokai at Truk, Caroline Islands, 20 Nov 1942; note battleship Yamato in background

Enroute from Kavieng were four heavy cruisers of Cruiser Division 6 under Rear Admiral Aritomo Goto: Aoba, Furutaka, Kako, and Kinugasa.

The Japanese Navy had trained extensively in night-fighting tactics before the war, a fact of which the Allies were unaware. Mikawa hoped to engage the Allied naval forces off Guadalcanal and Tulagi on the night of August 8 and August 9, when he could employ his night-battle expertise while avoiding attacks from Allied aircraft, which could not operate effectively at night. Mikawa’s warships rendezvoused at sea near Cape St. George in the evening of August 7 and then headed east-southeast.

The Battle

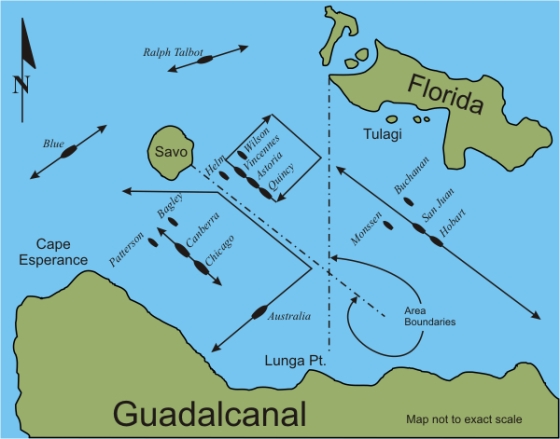

The western approaches to Savo Sound were guarded by a screening force of six heavy cruisers and six destroyer (the battle fleet had been destroyed at Pearl Harbor) in two groups covering both passages.

Radar pickets were the destroyers Blue (DD-387) and Ralph Talbot (DD-390) deployed west of Savo Island.

The south passage was defended by HMAS Australia (flagship of RAdm Crutchley, RN), HMAS Canberra, Chicago (CA-29), Bagley (DD-386) and

The northern group was made up of Vincennes (CA-44), Quincy (CA-39), Astoria (CA-34) and destroyers Helm (DD-388) and Wilson (DD-408).

The eastern approaches also had a screening force, made up of light cruisers San Juan (CL-54 flag), HMAS Hobart, and destroyers Monssen (DD-436) and Buchanan (DD-484).

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) 8th fleet of fast cruisers arrived the second night and met the US screening force for the Battle of Savo Island. At the same time, the three US carriers and their escorts, including North Carolina (BB-55), six cruisers, and 16 destroyers, were withdrawing to get out of sight of land-based bombers from Rabaul.

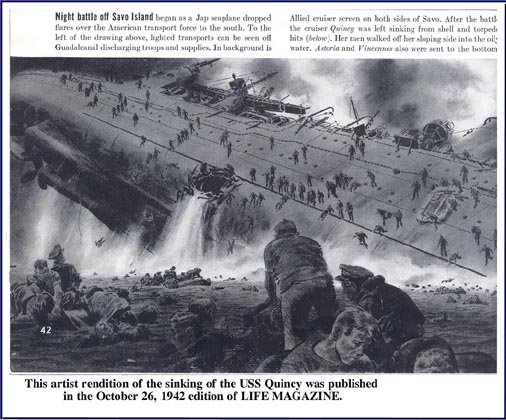

The enemy force of fast cruisers sent out scout floatplanes that reported the American forces. Both radar picket ships (radar range about 10 miles) were at the extreme ends of their patrols sailing away from the Japanese fleet which passed undetected about 500 yards from Blue. The enemy was lost in the visual and radar shadow of nearby Savo Island. Allied ships were faintly silhouetted by a freighter burning far over the horizon. The enemy discovered the southern force and fired torpedoes before they were detected. Simultaneously with the explosions, the scout plane dropped flares illuminating the allied fleet. Canberra was stuck by two torpedoes and heavy shelling. The US ships fired star shells and opened fire. Chicago of the southern force was torpedoed. The Japanese force turned north in two columns. The northern defense force had not gotten the word, there was a rain squall in the area, and they assumed the southern force was shooting at aircraft. The two Japanese columns passed on each side of the US force and opened fire on Astoria, Quincy, and Vincennes. The American captains ordered “cease fire” assuming they were Americans firing on their own ships. Vincennes caught a torpedo. Robert Talbot came charging south and was attacked first by friendly fire and then raked by the enemy escaping to the north. Quincy and Vincennes went down. During rescue operations for Canberra, Patterson was fired on by Chicago. Canberra was sunk the next morning to prevent capture as the US fleet left the waters that was hereafter called Iron Bottom Sound. Astoria sank about noon while under tow. Chicago had to undergo repair until January 1943.

The clear victor at Savo Island was Japanese Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, but he failed to follow up on his triumph.In just 32 minutes the enemy had inflicted massive damage. Four heavy cruisers were sunk and a heavy cruiser and destroyer badly damaged. 1,270 men were killed and 708 injured. The enemy had comparative scratches on three cruisers.

The Aftermath

A formal United States Navy board of inquiry, known as the Hepburn Investigation, subsequently prepared a report of the battle. The board interviewed most of the major Allied officers involved over several months, beginning in December 1942. The report recommended official censure for only one officer: Captain Howard D. Bode (USS Chicago). The report stopped short of recommending formal action against other Allied officers, including Admirals Fletcher, Turner, McCain, and Crutchley, and Captain Riefkohl. The careers of Turner, Crutchley, and McCain do not appear to have been affected by the defeat or the mistakes they made in contributing to it. Riefkohl, however, never commanded ships again. Captain Bode, upon learning that the report was going to be especially critical of his actions, shot himself in his quarters at Balboa, Panama Canal Zone, on April 19, 1943, and died the next day. Crutchley was gazetted with the Legion of Merit (Chief Commander) in September 1944. Admiral Yamamoto signaled a congratulatory note to Mikawa on his victory, stating, “Appreciate the courageous and hard fighting of every man of your organization. I expect you to expand your exploits and you will make every effort to support the land forces of the Imperial army which are now engaged in a desperate struggle.” Later on, though, when it became apparent that Mikawa had missed an opportunity to destroy the Allied transports, he was intensely criticized by his comrades. Admiral Turner later assessed why his forces were so soundly defeated in the battle:

“The Navy was still obsessed with a strong feeling of technical and mental superiority over the enemy. In spite of ample evidence as to enemy capabilities, most of our officers and men despised the enemy and felt themselves sure victors in all encounters under any circumstances. The net result of all this was a fatal lethargy of mind which induced a confidence without readiness, and a routine acceptance of outworn peacetime standards of conduct. I believe that this psychological factor, as a cause of our defeat, was even more important than the element of surprise”.

Check out my other blog

Check out my other blog I'M PUBLISHED

I'M PUBLISHED I'm Published Again

I'm Published Again

A reference librarian came through and found the entire poem for me. I have updated this post to include the entire poem.

LikeLiked by 2 people