On May 11, 1934, a massive storm sends millions of tons of topsoil flying from across the parched Great Plains region of the United States as far east as New York, Boston and Atlanta.

The Great Plains were settled in the mid-1800s when the land was covered by prairie grass. This condition held moisture in the earth and kept most of the soil from blowing away even during dry spells.

By two centuries later, farmers had plowed under much of the grass to create fields. When the United States entered World I in 1917, there was a great need for wheat and farmers began to push their fields to the limit, plowing under more and more grassland with the newly invented tractor. Americans were asked to conserve the consumption of wheat so that it could be shipped to support the troops.

U.S. Food Administration poster during World War I encouraging Americans to use cornmeal instead of wheat flour: “Patriots Use Corn Meal. It Cannot Be Shipped. It is Splendid Eating. It is Cheaper Than Wheat Flour.”

The plowing continued after the war, when the introduction of even more powerful gasoline tractors sped up the process. During the 1920s, wheat production increased by 300 percent, causing a glut in the market by 1931.

There was a severe drought spreading across the region in 1931. As crops died, wind began to carry dust from the over-plowed and over-grazed lands. The number of dust storms reported jumped from 14 in 1932 to 28 in 1933.

Map depicting dust storm damage from 1930 through to 1940. d. This map shows the states that were considered dust bowl states and the areas affected

The following year, the storms decreased in frequency but increased in intensity, culminating in the most severe storm yet in May 1934. Over a period of two days, high-level winds caught and carried some 350 million tons of silt all the way from the northern Great Plains to the eastern seaboard. According to The New York Times, dust “lodged itself in the eyes and throats of weeping and coughing New Yorkers,” and even ships some 300 miles offshore saw dust collect on their decks.

![Portrait shows Florence Thompson with several of her children in a photograph known as "Migrant Mother". The Library of Congress caption reads: "Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California." In the 1930s, the FSA employed several photographers to document the effects of the Great Depression on the population of America. Many of the photographs can also be seen as propaganda images to support the U.S. government's policy distributing support to the worst affected, poorer areas of the country. Lange's image of a supposed migrant pea picker, Florence Owens Thompson, and her family has become an icon of resilience in the face of adversity. However, it is not universally accepted that Florence Thompson was a migrant pea picker. In the book Photographing Farmworkers in California (Stanford University Press, 2004), author Richard Steven Street asserts that some scholars believe Lange's description of the print was "either vague or demonstrably inaccurate" and that Thompson was not a farmworker, but a Dust Bowl migrant. Nevertheless, if she was a "Dust Bowl migrant", she would have left a farm as most potential Dust Bowl migrants typically did and then began her life as such. Thus any potential inaccuracy is virtually irrelevant. The child to the viewer's right was Thompson's daughter, Katherine (later Katherine McIntosh), 4 years old (Leonard, Tom, "Woman whose plight defined Great Depression warns tragedy will happen again ", article, The Daily Telegraph, December 4, 2008) Lange took this photograph with a Graflex camera on large format (4"x5") negative film.[1]](https://mholloway63.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/lange-migrantmother02.jpg?w=560)

Portrait shows Florence Thompson with several of her children in a photograph known as “Migrant Mother”. The Library of Congress caption reads: “Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California.” Lange’s image of a supposed migrant pea picker, Florence Owens Thompson, and her family has become an icon of resilience in the face of adversity. However, it is not universally accepted that Florence Thompson was a migrant pea picker. In the book Photographing Farmworkers in California (Stanford University Press, 2004), author Richard Steven Street asserts that some scholars believe Lange’s description of the print was “either vague or demonstrably inaccurate” and that Thompson was not a farmworker, but a Dust Bowl migrant. Nevertheless, if she was a “Dust Bowl migrant”, she would have left a farm as most potential Dust Bowl migrants typically did and then began her life as such. Thus any potential inaccuracy is virtually irrelevant.

Another massive storm on April 15, 1935–known as “Black Sunday”–brought even more attention to the desperate situation in the Great Plains region, which reporter Robert Geiger called the “Dust Bowl.”

A photograph of an approaching dust storm in the Middle West; most likely in southwest Kansas. The southwest corner of the state was one of the hardest hit areas during the Dust Bowl. Dust storms, such as this one, rolled over the the southern Great Plains from 1932-1936, removing top soil from agricultural lands and prompting important changes in agricultural practice.

Creator: Conard, Frank Durnell, 1884-1966

Date: Between 1935 and 1936

That year, as part of its New Deal program, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration began to enforce federal regulation of farming methods, including crop rotation, grass-seeding and new plowing methods. This worked to a point, reducing dust storms by up to 65 percent, but only the end of the drought in the fall of 1939 would truly bring relief.

Woody Guthrie, The Dust Bowl Blues

Mumford and Son, The Dust Bowl Dance

If you have an interest in this topic, I highly recommend the documentary by Ken Burns, The Dust Bowl. He is well known for his films on the Civil War and Baseball, and the Dust Bowl is just as well documented.

Check out my other blog

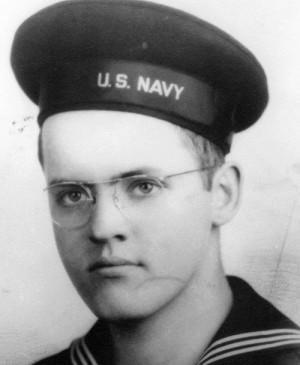

Check out my other blog I'M PUBLISHED

I'M PUBLISHED I'm Published Again

I'm Published Again

An awful time in our history, but what would emerge from the rubble became the Greatest Generation!

LikeLike

Very true. They endured a lot and were stronger because of it.

LikeLike

I did watch that documentary and it was very revealing and deeply touching. I knew of the devastation of the people and the land but did not have a full understanding how it came about and did not know that that the dust travelled so far

LikeLike